The History of Coqualeetza Hospital "Building 1"

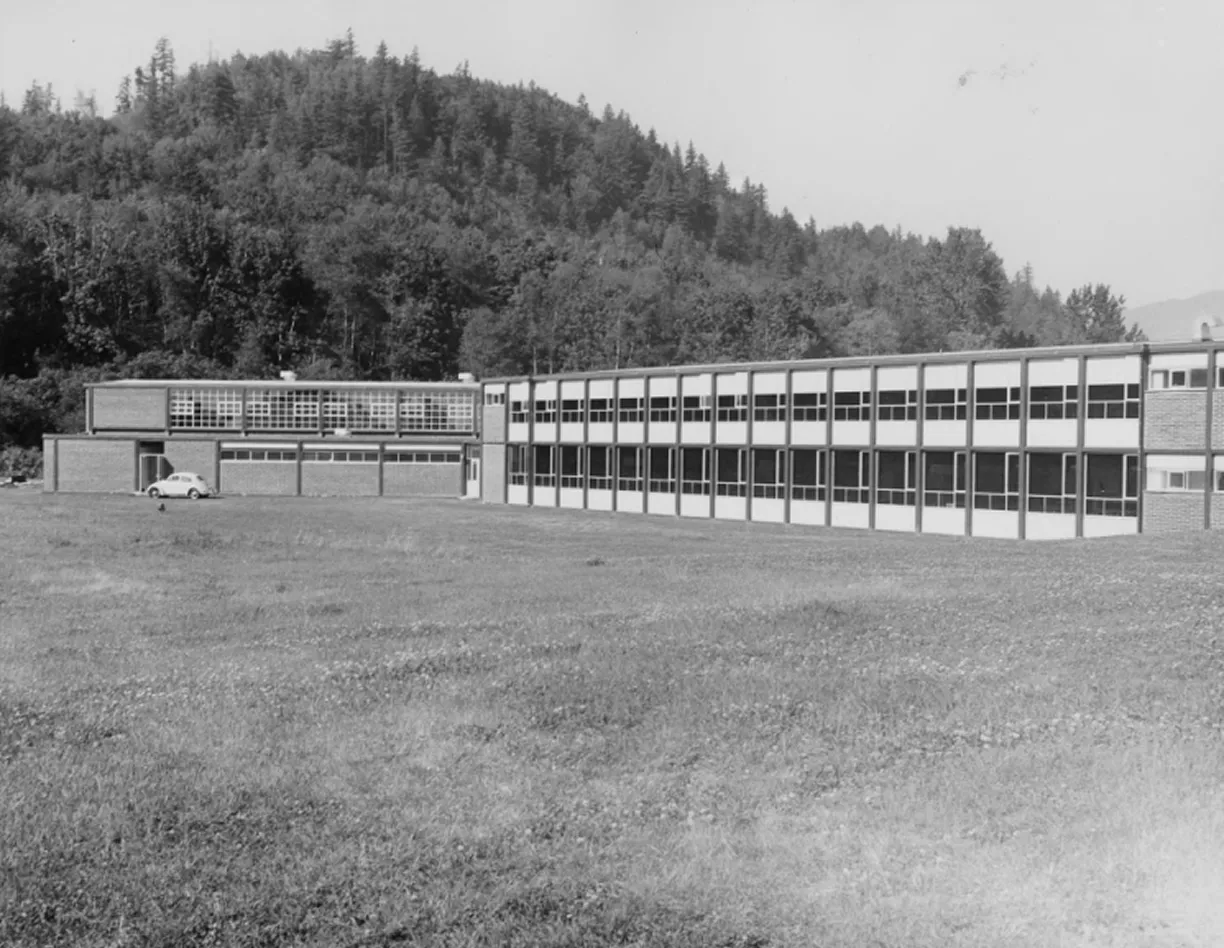

Situated on the Coqualeetza Grounds in Ts’elxwéyeqw territory in S’ólh Téméxw, the Coqualeetza Indian Hospital operated from 1941 to 1969. Following the closure of the hospital, the building itself took on many uses, including its use as administrative offices.

Meet the Stó:lō People of the River - Our Story

As part of OMNI Television's Indigenous Interstitial series, Patti Victor (Co-Director of Institute of Indigenous Issues & Perspectives at Trinity Western University Siya:m) shares the history of the Sto:lo People and walking the path to reconciliation in Canada.